A sermon on Acts 4: 32-35, John 20: 19-31, and Psalm 133, preached at Wesley Memorial UMC on April 12, 2015, during weekend festivities for the Wesley Foundation at UVA’s 50-year Celebration and Groundbreaking.

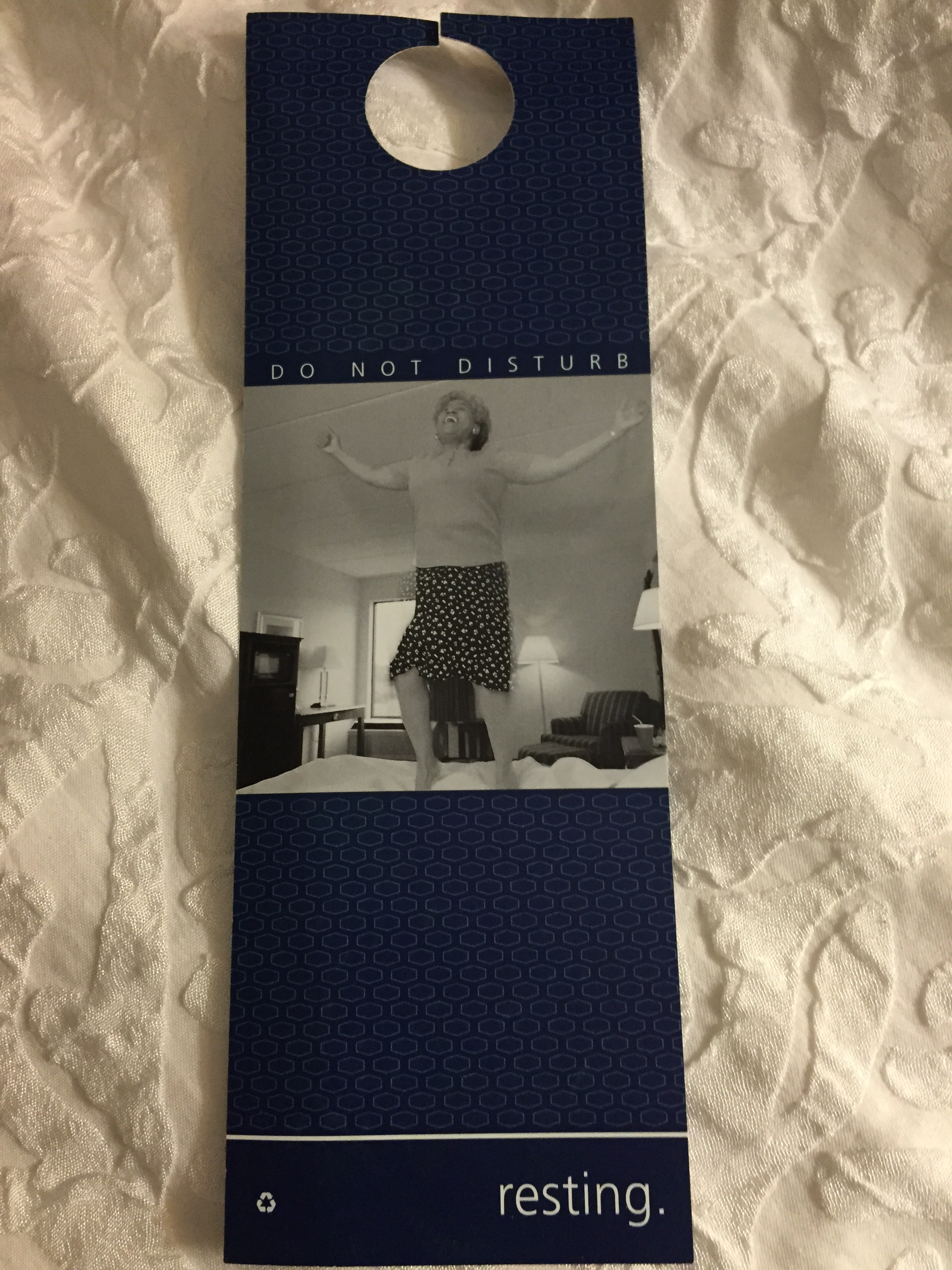

One of the Wesley bakers, with dairy-free, gluten-free bread fresh from the oven.

In my twenties I often concocted dream visions of communal living. Visiting with Wesley Foundation friends or Appalachia Service Project friends, we would revel in our reunion weekends, drink up the goodness of being together again, and plot our Someday dreams…a retreat center and intentional community in a big farmhouse with a huge kitchen table, a garden, and a writing shed for me, a little removed from the bustle….a self-sufficient community where we could grow our own food, make our own furniture, create all the pottery for our kitchen… These were dreams born from tight communities of faith formed at pivotal times in our lives, and that remained touchstones for all of us, no matter the time or distance. Whenever we got together we just wanted more. Not to go “back” exactly, but to create again that sort of Spirit-infused, life-defining, deeply communal expression of faith and love.

In none of these scenarios was I thinking explicitly of today’s passage from Acts. In all of these times I was remembering how good and full a community I had left, how lovely it was to dwell together in unity (to quote the psalmist). We had come together in a thin place – what Celtic spirituality calls those spaces where heaven and earth seem to be closer and more permeable to one another than usual – and in that thin place, we’d made thick, substantial, meaty community. We had seen glimpses and flickers of God’s kingdom made manifest and those were enough to sustain visions and lives.

When I think of the book of Acts, this is the passage I most often think of, though, we have to acknowledge, this idyllic time didn’t last that long. This time when no one held private possessions and no one was needy didn’t last. But it was thick and real while it lasted. It was important enough to describe and include in scripture so no one would think Did that really happen? Was I merely dreaming?

There are many thin places in the world but we are often too busy to notice them.

There are fewer thick communities and they can be so rare that we’re tempted to think we dreamt them.

We’re celebrating 50 years of ministry at the Wesley Foundation this weekend. It isn’t 50 years total but 50 in our current building, which we’re renovating and showing some TLC this year. Thanks to Ed for inviting me to preach here in the midst of this weekend as part of the celebration – how fitting, since Wesley Memorial has been our partner in campus ministry since the beginning. We had 200 people worshipping and celebrating here yesterday, alumni from at least as far back as 1963, “Wesley legacy” families with parents and children who’ve all made Wesley home, the Bishop, our district superintendent, students, and tons of friends.

Those of us celebrating yesterday and many of you here know the Wesley Foundation as a thin place. It’s holy ground, a thin place that’s home to a thick community with permeable boundaries, always being re-formed as people graduate and matriculate.

A couple of weeks ago the Wesley Foundation’s Student Coordinating Council (SCC) met for its “changeover” meeting, our peaceful transfer of power from one group of student leaders to the next. One of our practices at that meeting is to offer words of gratitude for those rotating off the SCC. At one point, in the midst of a long list of wonderful attributes and things she would miss about departing a student, one student stopped herself and blurted out, “How are you real?”

In some ways this is what Thomas needed to know and see and feel for himself, when he met the resurrected Jesus. How is any of this real? Do you remember what Jesus does? He does not refer to Thomas as a doubter or chastise him in any way. He simply offers up the most visibly wounded part of his body and invites Thomas to stick his hand all the way in and get a good, tactile feel for it. Thomas doesn’t even have to ask; he just has to reach out in the direction of the living, very real Christ.

How are you real? Here, see for yourself.

At its best, this is what campus ministry is: an invitation to see for yourself, in the midst of a community thick with the Spirit of the living Christ. It’s the kind of place where people are transformed, where they become more fully who God is calling them to be and, though it may only last 4 years, it’s enough to sustain a vision for the future.

Let me hasten to add, about that early Christian community in Acts and about the Wesley Foundation, that there’s nothing out of the ordinary about the people involved. Don’t get me wrong: I love me some Wesleyanos! But what I mean is, those early Christians weren’t somehow the cream of the crop, and though UVA students are the cream of the crop in many ways, Wesley folks aren’t the cream of the cream. That’s not what makes the community faithful or memorable or life-transforming. What makes both the Acts community and the Wesley community thick communities is the presence of the living Christ. It’s not the prefect storm of personalities and skills, dreamers and engineers. It’s Jesus.

How are you real? Jesus. The “thickening agent” in this recipe of love is the risen Christ.

The point of highlighting this long-ago and short-lived community from Acts isn’t to show what exceptional people they were. It’s to show what’s possible when the center of your life and community is the living Christ. The point is not that they were particularly un-needy people but rather that living with Christ at the center meant they prioritized the needs of others, they treated one another like family.

As I read our scripture passages this week I was struck by how physical and tangible the images are in each one. The risen Christ offers the wound in his side to Thomas. Surely the Acts community prays and worships together but we hear how they “bear powerful witness to the resurrection” (v. 33) by sharing things, the tangible goods they owned; they sold houses and properties and gave the proceeds to the group, to be used to purchase what they needed; people were housed and fed and clothed. And Psalm 133 offers us the messy but luxurious image of Aaron’s long, thick, bushy beard, claiming that living together as one is like expensive oil poured over his head and running through that big beard, soaking it through. Like I said, it’s messy, but it’s hard to read that and then think that spiritual things are separate and apart from physical things.

It’s also hard to read these passages and think that being faithful, being Christian is merely “between me and God.” Part of what is real and tangible about God in these stories is that God is made manifest in Christian community….in living together as family…in making sure no one among us is needy…in offering breath, touch, forgiveness, sharing our vulnerable and wounded selves with one another…

The reason we had 200 people here yesterday is because this is a place and a people who have embodied life with the risen Christ. People from across the decades are still savoring the thin place and space of their time at Wesley. Students are fed here, literally, every Thursday night. They stay up late together in Study Camp, offer rides home in the dark. They take each other to the hospital, offer hugs on hard days, and water on hot mission trips. Some meet their future mates here. We welcome strangers – every fall when new students arrive, and many other times when someone comes in crisis, or when other religious groups fall short and they are looking for a faith community where they can be and become all of who God made them to be.

One of the clearest recent examples of “no needy persons among us” is our Communion bread. At the 5pm worship service we celebrate Communion every week, gathered around the Table, offering the elements to one another around the circle. It’s a highlight and an orienting moment in each week.

But in the past few years we noticed we were meeting more and more students with gluten sensitivities, celiac disease, and some folks who both gluten-free and dairy-free. We struggled along for a while, using a little side plate on the Table to feed those who needed special bread at Communion. It seemed like the best we could do.

Until a student asked if she could try making a loaf we could all eat. There are two very important things to say about this endeavor: 1) It took her and a few other dedicated bakers experimenting for several weeks before we settled on the recipe we now use. Those early loaves were not all pretty or as tasty as what we have now. So, it wasn’t “perfect” from the start. And 2) The second thing to say is the one who offered to bake was not one of the students who had food allergies. She herself didn’t need the bread to change for her own health – she wanted to do this so that there would be no needy persons among us.

These are the moments I hear students and alumni recount decades after their years here. Deep spiritual moments expressed in physical ways, in the context of community…She remembered my name, he gave me a ride, they listened when I vented about my roommate, they didn’t laugh when I said I was thinking of going to seminary, they made bread I could eat, too…

Real, tangible bread, offered so that all could eat. That’s what a community thick with Christ looks like – that’s what it tastes like! That’s how love ends up looking like a round loaf of bread glistening with coconut oil on its crust. That’s the simple but extravagantly grace-filled type of thing that keeps this a thin place thick with the love of Christ. That’s why four years is a short time but long enough to send us out into the world and the rest of our lives, with the beacon of this community to orient us and the taste of heaven on our tongues.

Thanks be to God!

*

photo credit: © 2015 Aaron Stiles. Used with permission.